In an earlier article I have argued that Organizational Change Management is a discipline and not a leisure activity. Here I would like to focus on the part where it gets real: execution and how to get all that stuff done in practice.

In short: in order to be successful, organizational change efforts are not exercises in democracy but rather military deployments. This article builds further on that military metaphor to clarify my point.

Lessons Learned from Silicon Valley

In the chapter “On The Beach” of his 1993 book Accidental Empires, Robert Cringely talks about the three distinct groups of people that define the lifetime of a company: Commandos, Infantry, and Police. Whether invading countries or markets, the first wave of troops to see battle are the commandos. A start-up’s biggest advantage is speed, and speed is what commandos live for.

They work hard, fast, and cheap, though often with a low level of professionalism, which is okay, too, because professionalism is expensive. Their job is to do lots of damage with surprise and teamwork, establishing a beachhead before the enemy is even aware that they exist. Ideally, they do this by building the prototype of a product that is so creative, so exactly correct for its purpose that by its very existence it leads to the destruction of other products. They make creativity a destructive act.

Grouping offshore as the commandos do their work is the second wave of soldiers, the infantry. On big projects these are the multitudes of ‘big 5’ consultants who get the job done: blueprinting, designing, testing, training, collecting and cleansing data, etc. The most important thing here is that an infantry takes on a structured approach. In the words of Cringely :

While the commandos make success possible, it’s the infantry that makes success happen. These are the people who hit the beach en masse and slog out the early victory, building on the start given them by the commandos. […] Because there are so many more of these soldiers and their duties are so varied, they require an infrastructure of rules and procedures for getting things done.

What happens then is that the commandos and the infantry head off in the direction of Berlin or Baghdad, advancing into new territories, performing their same jobs again and again, though each time in a slightly different way. But there is still a need for a military presence in the territory they leave behind, which they have liberated. These third-wave troops hate change. They aren’t troops at all but police. They want to fuel growth not by planning more invasions and landing on more beaches but by adding people and building economies and empires of scale. They can’t even remember their first- and second-wave founders.

UN Peace Keeping Troops

To my experience, this same distinction applies to big organizational change projects. However, in order to make this approach effective in that context, Cringely fails to notice that you need UN Peace Keeping Troops between the infantry and the local police.

Once your prototype is ready to be tested, you will find that UN Peace Keeping Troops are quintessential in order ‘to get organizational change management done’. This is the fragile process of handing over knowledge from project agents (infantry) to the target users (police and citizens) and to manage the process of political buy-in.

In most of the SAP projects where I am involved we call them ‘local coaches’ or ‘transition teams’ They manage the fragile process of handing over knowledge from project agents to the target users. Their only purpose is to stabilize the new order and eventually to hand over to the local peacekeepers: the police.

A Best Practice from SAP Implementations

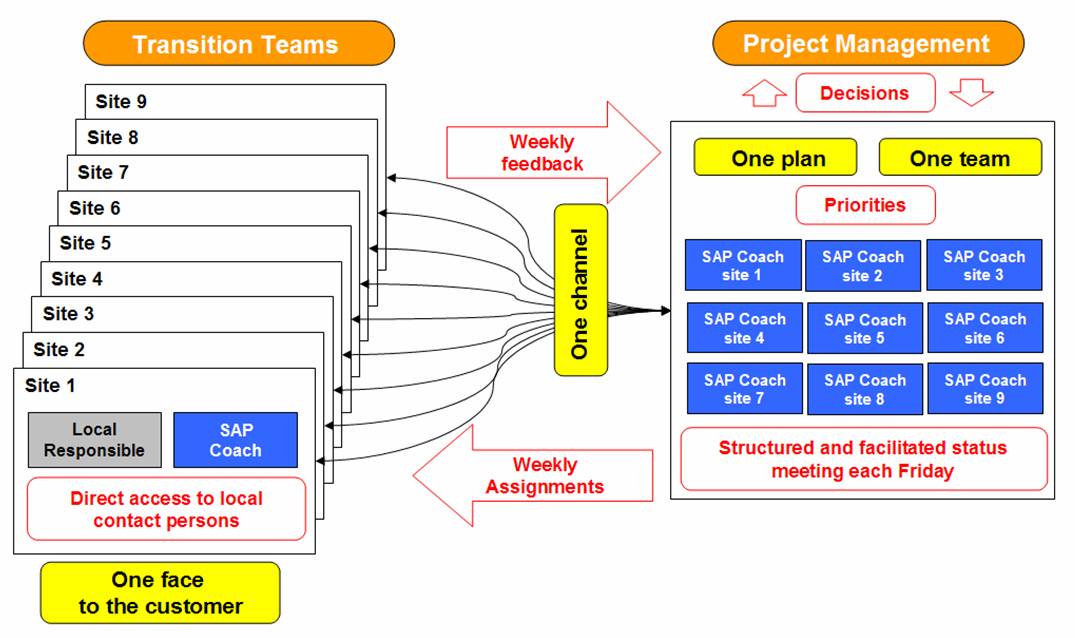

The below drawing shows a model that I would tag as ‘best practice’ because I have been refining it over the course of multiple projects. The yellow boxes indicate the basic principles we want to achieve.

Examples of typical coaching assignments include the following:

- Attaching people to new functional roles and having the subsequent trainings validated

- Communicating the vision and strategy and translating these to the level of the site (‘does this make sense to you?’)

- Communicating the future processes and highlighting the what’s in it for me (WIIFM)

- Local testing of processes

- Implementation and follow up of key performance indicators (KPIs)

- Following up data collection and data cleansing

- Supporting local training initiatives and evaluate the learning of the users after they went to training

- Assisting with the local technical systems deployment

The most important thing is to note that underneath these examples are some fundamental ‘soft’ returns on investment:

- By their physical presence and time they spend locally the coaches can do the job of ‘handholding’ that is necessary in times of change

- They provide psychological safety by translating the central concepts to local practice

- UN Peace Keeping Troops leverage the impact of the experts in the central team on a local level because they have direct access to all implementation team members

- If you gather them on a weekly basis and if you facilitate their weekly meeting, they will accelerate best practices and stick to common standards.

UN Peace Keeping Troops need to be there to prevent simple things from going wrong and to help people make their first small victories in ‘real life’.

Pingback: Community Development is the New Change Management | Reply-MC()