In my last post, I talked about moving past basic motivators for being in this line of work, and hinted at the fulfillment that comes from applying one’s professional talents to a greater good.

We each have our deeper reasons for engaging this work. To encourage you to think about yours, I’ll share mine. Here are the major reasons I think it’s important to be a change practitioner.

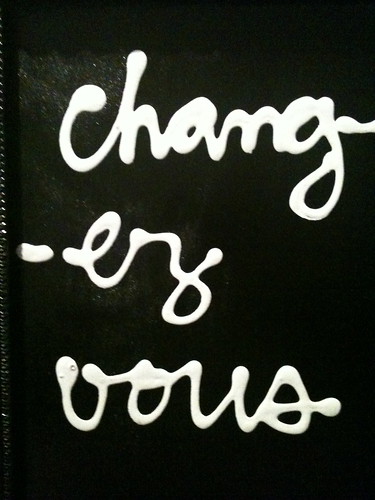

The challenge of change grows…relentlessly.

No aspect of human existence is protected from the unending avalanche of change that continues to escalate in magnitude, complexity, and far-reaching, interdependent implications.

It’s not simply more of the same. Changes now and in the future will ask more of us.

Einstein said, “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” Without new perspectives on the difficulties/opportunities we encounter and ingenious ways to address them, there is no hope of elevating the level of thinking to what is needed.

Too much inventiveness, however, can also be a problem. For example, many leaders feel they are charged with executing initiatives that they don’t fully understand and/or believe in. To accomplish major change in today’s world, we not only need creative solutions, we need people to fully grasp and support them.

Whether they initiate change or respond to it, people struggle the most with the execution of their plans.

Knowing how to successfully orchestrate a transition is just as vital as correctly determining what to change, yet implementation is typically the more neglected of the two skills. For most people, this has led to a significant gap between their ability to identify what solution to pursue and their ability to actually accomplish their intentions.

The true cost for this “what/how” skill variance comes to light when there is poor implementation of changes that could make a difference.

Despite the rhetoric that accompanies the majority of new endeavors, in the grand scheme of things, most attempts to change or respond to change have little long-lasting impact on people’s lives. Some undertakings, however, could make a significant, positive difference in the quality of life (and even protect life itself) if only they could be fully realized. These are the changes that matter…the ones we must ensure are successfully executed.

Today, the number and criticality of changes that matter is higher than ever before. Sometimes the issues being addressed are massive: local/global economic challenges, environmental degradation, starving multitudes, or the inhumanities one group of people inflicted on another.

Other times, the scope of impact is limited to an individual or small group, but the implications are no less critical for whoever is affected. Changes that matter are the ones intended to have a positive impact on the course of history, whether the beneficiary is a person or all of humanity. The problem is that, too much of the time, solutions of this nature are derailed because of weak execution.

It’s not enough to be well intended. Important changes must be actually realized.

Changes that matter generate great value on their own, but there are additional, secondary benefits that happen each time important initiatives are successfully executed.

- People believe more in creating new possibilities because they have confidence that innovative ideas can translate into tangible results for individuals, organizations, and society.

- People learn that it’s possible to be personally resilient and organizationally nimble when faced with significant change.

- People see that complexity and ambiguity can be managed and used to their advantage.

- People affected by change don’t feel victimized, and the credibility of those leading the efforts is strengthened.

- People are able to apply lessons learned in one setting (i.e., an organizational environment) when they encounter change in other aspects of their lives.

- People learn they have a greater capacity for courage and discipline than they realized.

Changes that matter come in many forms and domains (social shifts, geo-politics, technology, healthcare, environment, business, etc.), but what they all have in common is the imperative nature of their implementation.

Because of the positive implications if successful, and/or the negative repercussions if not, there is a prohibitively high price tag for these kinds of efforts failing to reach realization.

Learning to guide these kinds of transitions toward their intended outcomes is more than a good idea. The caliber of life—in fact, the very survival of the human species—depends on people becoming architects of, rather than overwhelmed by, change.

Few people are proficient enough at orchestrating or responding to transitions to successfully execute today’s changes that matter, much less the important ones just over the horizon.

Because of the ever-accelerating pace and sophistication of change, even people with honed implementation skills and a high tolerance for ambiguity will find themselves, at some point, underprepared for the level of turbulence they will face. As a result, whether people are aware of it or not, everyone needs more effective ways to navigate change.

Organizations provide excellent settings for learning how to successfully execute important change.

Professional change practitioners are positioned to help people acquire the knowledge and skill needed to accomplish changes that matter. The high concentration of people, the practical nature of the initiatives taking place, and the measurable impact of success and failure makes a person’s work environment an ideal place to learn how to advance implementation-related knowledge and skills.

There is plenty of justification for applying these lessons to an organization’s initiatives. An even greater payoff comes, however, when people realize that their place of work can serve as a learning laboratory for what can be applied far beyond organizational boundaries (with family, local community, government, or social action causes, for example).