“How much do you love me?’ and “Who’s in charge?” ….these two questions of LOVE and CONTROL undo us ALL, trip us up and cause war, grief, and suffering. (Elisabeth Gilbert)

In his recent book Helping: How to Offer, Give, and Receive Help Edgar Schein demonstrates that we learn early in life about two fundamental cultural principles which he summarizes as Social Economics and Social Theatre. The purpose of this article is to dissect the different building blocks of human interaction and both of Schein’s principles turn out to be a perfect starting point for that.

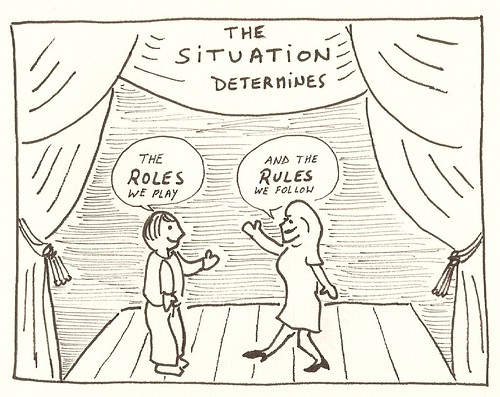

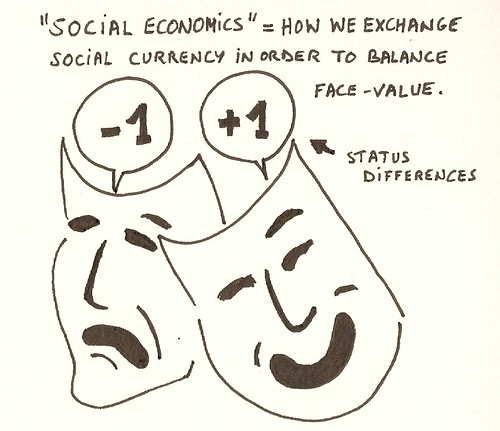

The normal process of daily life is a series of situations that tell us what roles we should play and what to expect of others – this is the theatre part. Next to that, people want to behave according to the status of the participants and the situation – this is where economics comes in, because status differences are paid for with a social currency.

Social Theatre

All relationships are based on scripted roles that we learn to play early in life. We must play our roles appropriately and they must fit the situation we are in.

The degree to which the metaphor of theatre dominates our thinking can be illustrated by the language we use to describe social interactions:

- playing your part of the conversation;

- feeding someone a line;

- ask what someone’s role is;

- presenting a scenario;

- counting on someone to perform;

- claiming we have heard that song before;

- getting the show on the road;

- stealing the show;

- getting your act together;

- acting your age;

- setting the scene for a meeting;

- asking what is going on backstage;

- etc.

The normal process of living can be seen as playing out a set of scenes in which we act out appropriate behavior. According to Schein:

In daily life we have learned thousands of roles and scripts so that we can go smoothly through the process of identifying the various situations that we encounter or create and manage the different relationships in which a typical day will plunge us.

If I signal that I have something important to tell you, this defines the situation, the roles and the interaction. You automatically take an attentive attitude.

Social Economics

Schein also notes that it is funny to see how much of the social economics of relationships is embedded in the daily language we use when we refer to human interaction. For example:

- Paying attention

- Paying respect

- Pay a compliment

- Investing in relationships

- Building social capital

- Sell your point of view

- Buy good-will

- Not buying an unlikely story

- Owe the courtesy of a reply

- Lend an ear

- Borrow strength

It seems like all communication between two parties is a reciprocal process that must be fair and equitable. We say “thank you” when we are given something. Saying ‘thank you’ closes the communication loop and makes the interaction fair and equitable. Another example: if someone asks for assistance we are obligated to respond. We respond to the request either by granting help or by offering an excuse to explain why we are not helping the other person.

The opposite is also true: if someone offers help, the person to whom it is offered is obligated to accept it or offer some excuse for not accepting it. Not responding is not an option in daily life; it would feel very un-natural.

A request requires a response and an offer requires a ‘thank you’.

When we take a closer look we see that this simple dynamic of reciprocity is the engine that drives human interaction: our self-esteem is based on acknowledgement of the value of the face we claim for ourselves. This is called ‘face-value’. In this respect, Schein notes:

This process of perpetual mutual reinforcement is the essence of society. What we call good manners or etiquette is in fact culturally necessary in daily life.

Here is an experiment you should try for yourself: observe your daily interactions with other people and see if you can recognize that each situation determines the roles you play and the rules you follow. Also note how every request requires a response and see what happens if you simply give a blank face and no response at all to the person who is asking ‘How are you doing?’

Series Navigation

Unraveling Social Interaction (Part 2) >>

Pingback: Unraveling Social Interaction (part 7) | Reply-MC()