Who could have known that in order to find out the influence of national culture on human interaction one needs to investigate the cockpit transcripts of plane crashes?

The Ethnic Theory of Plane Crashes

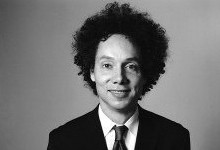

In his book Outliers: The Story of Success Malcolm Gladwell included a chapter on ‘The Ethnic theory of Plane Crashes’. Gladwell dives deep into the investigations of plane crashes of Korean Air, Avianca and Florida Air and zeroes in on the cockpit transcripts. Some time ago I had the chance to interview him on the importance of culture and communication inside cockpits.

Gladwell analysed the dialogues between the crew and traffic controllers and found that when we ignore culture, airplanes crash.

Deference and Demeanor

Let’s have a closer look at the dynamics of human interaction between a captain a first officer in a cockpit. Their relationship will follow the laws of deference and demeanor. Deference and demeanor are widespread sociological theories, developed by Erving Goffman in his essay ‘The Nature of Deference and Demeanor’. He defines demeanor as the way a person acts, and deference as the respect and/or reaction another person has to that behavior. In other words: deference and demeanor determine the face value that should be acknowledged in a certain situation.

Knowing that each situation determines the face-value that we can claim for ourselves, the relationship between a captain and a first officer should not contain any ambiguity, right? Yet, once they are up in the air the situation may change in such a way that they are confused about what they should acknowledge or claim.

Mitigated Speech

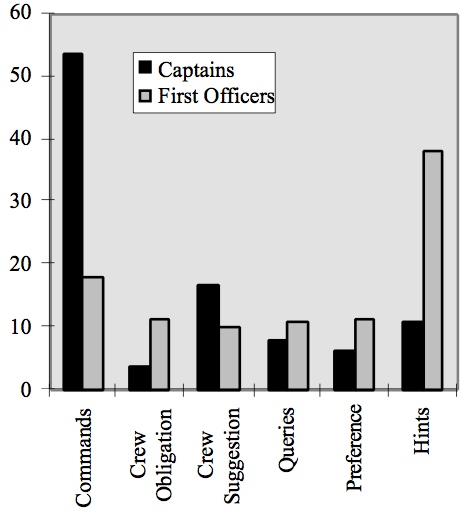

In their 1999 study Cultural Diversity and Crew Communication Fischer and Orasanu tried to identify effective communication strategies for calling attention to problems and getting action on them from other crew members who differ in rank, culture, and gender. One of the methods they used was to measure how they would correct different pilot errors in a particular situation. Both, pilots and first officers were given 6 classes of requests to choose from:

- Commands: “Turn 30° right”.

- Crew Obligation Statements: “I think we need to deviate right about now”.

- Crew Suggestions: “Let’s go around the weather”.

- Queries: “Which direction would you like to deviate?”

- Preferences: “I think it would be wise to turn left or right”.

- Hints: “That return at 25 miles looks mean”.

In Outliers, Gladwell refers to these categories as the 6 degrees of mitigation with which we make suggestions to authority. Mitigated speech is a linguistic term describing deferential or indirect speech inherent in communication between individuals of perceived High Power Distance. Gladwell describes the term as:

Any attempt to downplay or sugarcoat the meaning of what is being said.

Fischer and Orasanu discovered that lower-ranking crew members are frequently unsuccessful in getting the attention of a higher status crew member or in getting senior crew members to change their decisions or actions in safety-critical situations. It’s no surprise that captains generally preferred commands while first officers predominantly used hints.

Their study underscores how difficult it is to overcome ingrained norms for interacting with superiors and subordinates.

PDI – Power Distance Index

To make things worse, the influence of national culture reinforces the dynamics of deference and demeanor in aviation communication. In this respect Gladwell refers to Geert Hofstede who built his cultural dimensions theory between 1967 and 1973. Hofstede gathered and analyzed extensive data on the world’s values and cultures and mapped them on six dimensions:

- Power (equality versus inequality),

- Collectivism (versus individualism),

- Uncertainty avoidance (versus tolerance),

- Masculinity (versus femininity),

- Temporal orientation, and

- Indulgence (versus restraint).

The first dimension, Power Distance Index (PDI) is an important one for captains, first officers and traffic controllers. PDI measures the extent to which the less powerful members of an organization accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. Countries with a low PDI prefer small power distance relationships and in high power distance countries less powerful people accept power relations that are autocratic and paternalistic.

It turns out that every attempt to reduce power-distance in the cockpit is highly influenced by the power-distance that is dictated by our national culture. The investigation of three particular transcripts of air plane crashes illustrate the devastating influence of national culture.

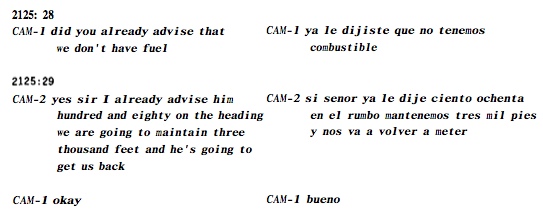

Avianca Flight 052

On January 25, 1990, an Avianca Boeing 707 crashed in Cove Neck, New York, as a result of fuel exhaustion. Avianca Flight 52, a B-707, was bound from Medellin, Colombia to New York, JFK. The flight experienced three extended holding patterns due to bad weather up the Atlantic coast and at JFK. The fuel state was becoming critical by the end of the third hold. The intracockpit conversations indicate a total breakdown in communications by the flight crew in its attempts to relay the situation to ATC (Air Trafic Control).

The captain, the first officer and the traffic controllers were perfectly trained and there was no mechanical failure. However, the Colombian co-pilot is using his own cultural language, i.e. speaking as a subordinate would to a superior. The air traffic controllers are not high PDI Colombian but low PDI New Yorkers. They don’t see any hierarchical gap between the pilots and themselves. When there is no single currency of communication to calibrate the two cultures, disasters can happen.

To a New York traffic controller deferential speech doesn’t mean that the pilot is being appropriately deferential to a superior; it means that the pilot doesn’t have a problem. Gladwell notes:

Our ability to succeed at what we do is powerfully bound up in where we are from. And being a good pilot and coming from a high power-distance culture is a difficult mix.

It turns out that ignoring the cultural differences got eight of the nine crew members and 65 of the 149 passengers on board killed.

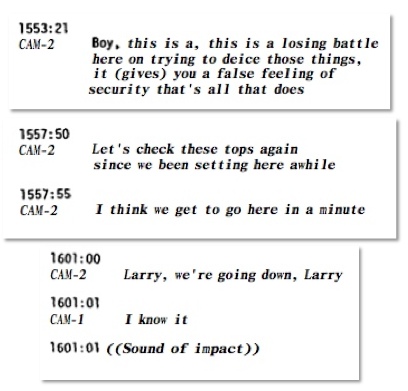

Air Florida Flight 90

On January 13, 1982, the Boeing 737-200 flying Air Florida Flight 90 crashed into the 14th Street Bridge over the Potomac River, killing all but four passengers and one flight attendant. This crash seems to be the result of ineffective mitigated speech of the first officer.

On multiple occasions he tries to hint, prefer, query and suggest to de-ice the wings of the airplane. All to no avail. The captain is not responding to his requests and the first officer is at the limits of appropriate deference for the given situation. The plane crashes at take-off.

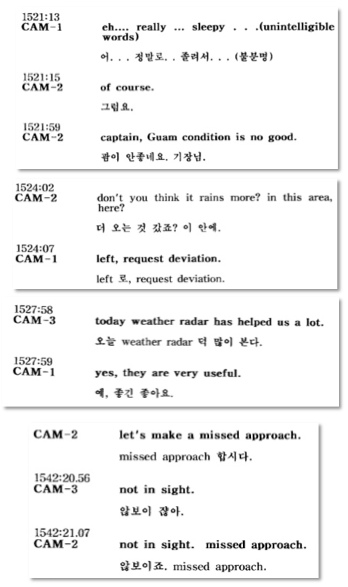

Korean Air Flight 801

Korean Air Flight 801 crashed on August 6, 1997, on approach to Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport, Guam (a United States insular area). The aircraft crashed on Nimitz Hill in Asan, Guam while on approach to the airport.

This particular crash illustrates the negative reinforcement of a high PDI culture on cockpit communication. We can only understand what has been going on in that cockpit if we take into account the characteristics of this high PDI culture. Apparently our Western communication has a transmitter orientation, i.e.: it is considered the responsibility of the speaker to communicate the sense of his message unambiguously. If there is confusion it is considered the fault of the speaker.

However the Korean language – like most Asian languages – is receiver-oriented. It is up to the listener to make sense of what is being said. For example, Korean language has six degrees of formal address:

- formal deference,

- informal deference,

- blunt,

- familiar,

- intimate, and

- plain

This leads to very subtle communication and the co-pilots being at the limits of formal deference for the given situation. The high PDI culture of Korea has a multiplication effect compared to the Air Florida cockpit.

Language Is The Key

To solve this problem, Korean Air brought in David Greenberg, a retired Delta Air Lines vice president, to run its operations. Greenberg’s first rule was that English should be the language of aviation. Greenberg started with the airline’s flight crews. He introduced rigorous new training and testing standards, as well as some ”cockpit culture” changes for Korean Air’s 1,700 pilots. On the ground, he began basing promotions and transfers in the company’s ranks on merit rather than connections and friendships.

Declaring English as the formal cockpit language – even among Korean pilots who are sitting side by side – gave the pilots an alternate identity. That way the pilots could escape the roles that were dictated by the heavy weight of their country’s cultural legacy. Gladwell notes:

They needed an opportunity to step outside those roles when they sat in cockpit; and language was the key to that transformation.

In English they would be free of the six gradients of Korean language. This transformed their relationship to their work.

The Lesson for Us?

Galdwell’s study made it clear that deference, demeanor and culture should be addressed in order to make planes safer. But what about less life threatening situations like running a multi-billion project or running a multinational company? The way we address culture is always though stupid surveys and never though effective communication strategies. We’ve got work to do. I guess this is why I am diving to deep into the dynamics of human interaction.