If we want to get more out of training programs we should redefine them as learning programs. Changing that one word can make the difference between the achievement or the failure of a strategic initiative.

A recent article of McKinsey Quarterly triggered me to review my own theory on training and learning. McKinsey uncovers some weak spots of training programs in general and relates these weaknesses to shortcomings on the level of leadership.

The article opens with the astonishing observation that:

Only one-quarter of the respondents to a recent McKinsey survey said their training programs measurably improved business performance, and most companies don’t even bother to track the returns they get on their investments in training. …/… The most significant improvements lie in rethinking the mindsets that employees and their leaders bring to training, as well as the environment they come back to afterward.

They conclude by saying that the ‘why’ of a training program is the most important element to ensure that the training objectives are being met. I applaude McKinsey for underscoring the role of a leader in making sure the ‘why’ of a program comes across, both: during the preparation of a training program AND in the return to the workplace.

Now, back to Luc’s world. Entering my world is easy because I tend to reduce reality until it fits into simple shapes (I love triangles) and simple equasions (three is my favorite number). When I approach change, training and learning this is no different. But bear with me, because I wil start with a simple triangle, cut it in three, turn it upside down and pour it into a cycle.

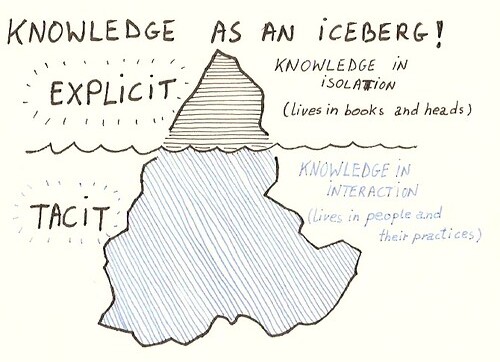

The Learning Iceberg

It is very easy for us to think that all knowledge is in the head, but we often ignore how much of our knowledge exists in action, participation with the world, participation with the problem and participation with other people, i.e., practices. A lot of the knowing comes into being through the practices of the people and the environment you’re working in.

According to John Seely Brown knowledge has two dimensions, the explicit and tacit. The visible part of the iceberg represents all the explicit information contained in instructions, procedures and manuals. This is the knowledge transfer, which garners the most tangible investments.

But the bottom part of the iceberg is much more important: the tacit knowledge as it lives within the organization. This knowledge cannot be classified in an orderly manner; rather it’s a pick and mix of all the formal knowledge featuring real issues, possible solutions, actions, war stories and your colleagues’ experience.

A manual or a procedure will not help you figure out whether a problem is important, or whether a solution is elegant, or whether it is even a solution. According to John Seely Brown, real knowledge is not taught, it is experienced in the form of unwritten stories and conversation.

The Three Ingredients

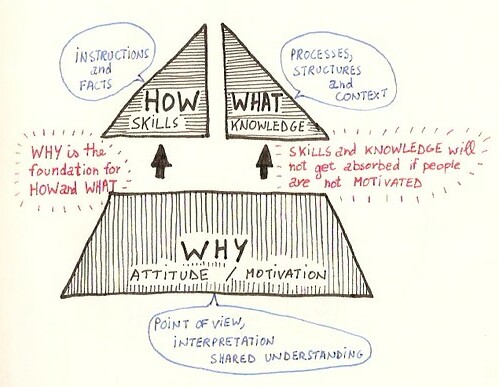

When we have a closer look at the knowledge iceberg, we see it is composed out of three ingredients: Motivation (the emotional stuff below the surface), Knowledge and Skills. These determine the domains of action for making the learning happen.

- Questions and reactions, which fall into the ‘Knowledge’ category, often indicate a need for vision, a business case or an overview. These refer to the ‘what’ of the learning.

- The ‘Skills’ category indicates a need for concrete and explicit knowledge, tools and working instructions. In other words: people want to know ‘how’ they will make the change happen.

- In addition there is also an entire range of reactions that fall into the ‘Motivation’ category (the underlying reason that drives the change: the ‘why’). These reactions reflect people’s need for involvement and inspiration.

Focus on Learning, Not Just Training

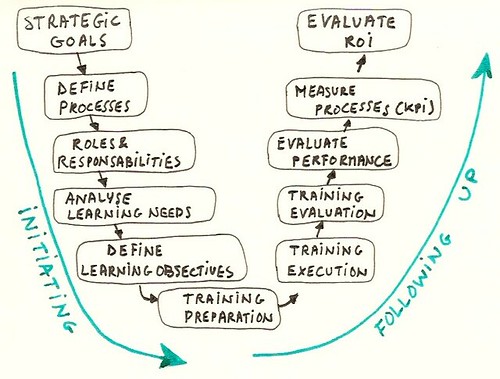

People often ask me why I always refer to ‘Learning’ instead of ‘Training’. That is because 99% of what ‘Learning’ really is occurs outside of the classroom. To illustrate, let’s have a look at the below learning cycle. All the stages are drawn in a chronological order. What’s more, each stage of the initiating part has a corresponding phase in the follow-up part:

- The strategic goal setting will eventually be measured and evaluated when the Return on Investment of a learning program is calculated;

- The processes that are designed will eventually be measured with performance indicators;

- The roles and function descriptions are evaluated in performance reviews

Embedded on the lower level of this learning cycle are the 5 stages of the training cycle:

- The learning needs need to be evaluated after the training

- The learning objectives need to be translated into the right training deliverables

- Finally, on the lowest level, the training preparation needs to make sure that the training gets done

This learning cycle emphasises the larger context of training programs: training strategically requires all training programs to be linked to strategic goals AND – for Pete’s sake – to be followed up. The focus on learning instead of training alone helps to achive that goal.

Why? Why!

In his 2008 book Strategy and the Fat Smoker; Doing What’s Obvious But Not Easy, David Maister claims that training is a wonderful last step in bringing about changed organizational and personal behavior, NOT a pathetically useless first step. Most firms go about training entirely the wrong way: they decide what they wish their people were good at, allocate a training budget and then ask the training manager to come up with a good program.

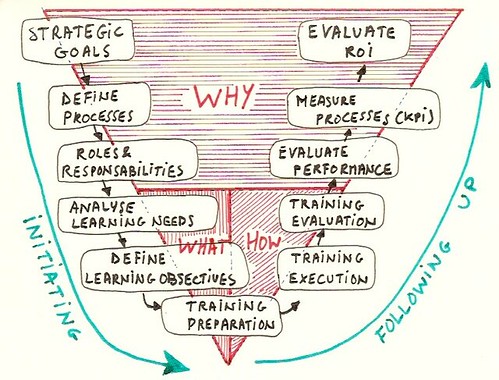

In the below diagram I have combined the three ingredients of learning with the learning cycle.

The first three stages and the corresponding last three stages represent the ‘why’ homework that is required of leaders in order to leverage the efforts of a training program into a learning program. The five blocks in the lower part represent the classic training cycle, an activity that – ideally – starts once it has been determined that the requirement at hand is a training need. Although training delivery is an art, one cannot expect more than “impeccable delivery” in an evaluation of the training.

The proof of the pudding is in the follow-up once participants are back in their working environment. Therefore Maister underscores the importance of the ‘why’ question. It is management’s job to make people ‘want’ to learn things by managing the ‘why’ – helping them understand why this important and fulfilling and why people should sacrifice their time and attention to get involved. The ingredient ‘Why’ determines whether people undergo a training or take part in a learning endeavour.

Instead of approaching training as active learners, many employees behave as if they were prisoners (“I’m here because I have to be”), vacationers (“I don’t mind being here—it’s a nice break from doing real work”), or professors (“Everybody else is here to learn; I can just share my wisdom”).

(quoted from the McKinsey study)

An often made mistake in training programs consists of postponing all contacts with the participants until the very last minute. As a result, people feel as if a concept is being forced upon them and they aren’t really given the time to fully comprehend it.

The knowledge provided during training is so theoretical that it has nothing in common with practice. Many of the people wonder why they have to spend all that time in training and are annoyed because their day-to-day work is just laying around. They have received all the explicit knowledge that is – rationally speaking – necessary to face the change. They have had the ‘what’ pushed down their throats. But the project grinds to a halt soon after that because people have not been given the time to participate and make sense of it all (the underlying ‘why’).

The inevitable truth is that people will need to tinker with the ‘why’ anyway in order for the program to work, so it is better to do that during preparation than to pay for it in terms of a sputtering go-live.

People should be given the opportunity to be part of the creative process that is expected from them. That is why it is necessary to effectively involve them before, during and after the training. Involve them – too simple to be true – and apparently too hard to commit to.

Participants rarely leave any training program entirely prepared to put new skills into practice. Old habits die hard, after all, so reinforcing and supporting new kinds of behavior after they are learned is crucial.

(quoted from the McKinsey study)

The above quote points out you need a ‘why’ in the beginning as a spark for building the momentum, but you need the same why-power when people come out of the classroom.

Unfortunately, executives take the training off their checklist when the training program has started and never come back to pull the results out of the training program. And this final consolidation represents the last 99% of the value of a learning program!

Making Why Work: The Three C’s of Learning

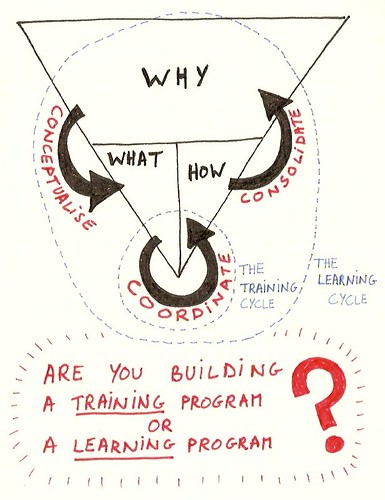

In his 1994 book The Empty Raincoat, Charles Handy introduces the three C’s of learning. They are conceptualizing, coordinating, and consolidating. according to Handy they are the essential mechanisms underlying personal, organizational and societal learning.

When we apply the three C’s on the triangle we just flipped we see that the three C’s are precisely the activities that is needed to jump the fences:

1. Conceptualizing: this is what you do when you translate the ‘why’ of an organizational goal into the ‘what’ of a learning objective;

2. Coordinating: this is what you do when you translate the ‘what’ of a learning objective into the ‘how’ of a training execution;

3. Consolidating: this is what you do when you link the outcome of the ‘how’ of a training back to the workplace requirement ‘why’ you started the learning program in the first place.

The three C’s are there for a reason. They underscore the moments where leverage is possible and courage is needed:

1. The courage to conceptualize results in a learning attitude: participants who pull out what they need instead of just attending;

2. The courage to coordinate results in excellent training execution: the training caters exactly for the needs;

3. The courage to consolidate results in the commitment to make it work when people return to their workplace.

The second C is what we could call the ‘efficiency’ of a training program: an art you can fully delegate to a proficient training manager. It is the art of executing the ‘what’ and ‘how’ a training program.

Leveraging the training program into a learning program will require the first and the third C to be successful as well. Note that the first and the third C are to a great extent the responsibility of managers: pushing the ‘why’ into a concept and pulling it back into the realm of the ‘why’.

When I say Learning

You can take my word for it: What looks like a training issue will turn out to be a learning issue in 99% of the cases.

If you want to get more out of training programs (the original question McKinsey attempted to answer in its article) you should aim for transforming them into a learning program.

The different wording is essential, because when I say “Learning”:

- I mean training coordination PLUS all the stuff that happens before and after: conceptualizing and consolidating

- I mean participants PLUS their bosses

- I mean the how, underscored by the what AND propelled by the why

- I mean the excellence of training execution PLUS the learning relationship between participant, leader and trainer.