In this article we look for handgrips to operationalize Sense of Community. We do so with the help of the Sense of Community Index. This survey will give us a better understanding of what cues to listen and look for and how to respond.

The Sense of Community Index version 2 (SCI-2) is based on the theory of David McMillan and David Chavis in 1986. The authors describe sense of community using four elements: membership, influence, meeting needs, and a shared emotional connection. Community Science developed this measurement tool to help assess sense of community.

The survey is composed of 24 questions that measure each of the dimensions of Sense of Community we have examined in the previous article. For each of the statements people are requested to respond to how well do each statement represent how they feel about their community on a 4-point scale of ‘not at all’ – ‘somewhat’ – ‘mostly’ – ‘completely’.

Let’s have a closer look at the statements because they tell us more about how people connect to a community. In other words: these statements provide handgrips or connection points. They tell us in terms of what cues to look for and how to respond.

Membership is about Identity

Membership is the feeling of belonging to a group because one has invested a part of oneself in order to become a member. In one way or another members are searching to find a part of themselves in the community. The statements of the survey dealing with this dimension are the following:

- I can trust people in this community

- I can recognize most of the members of this community.

- Most community members know me.

- This community has symbols and expressions of membership such as clothes, signs, art, architecture, logos, landmarks, and flags that people can recognize.

- I put a lot of time and effort into being part of this community.

- Being a member of this community is a part of my identity.

For all aspects of membership the real game-changer is the creation of roles within the community. Roles are the vehicle to bring structure to the membership-aspect a community. They make belonging and being together tangible and safe.

The psychology of roles within a community is really fascinating, because it affects many aspects of the self simultaneously:

- Emotional safety: roles grant permission to members to take certain initiatives.

- Boundaries: when you ‘wear the badge’ you become an agent of that role and this sets you apart from from those who don’t.

- Symbol system: before you know it, you will start to identify with your role(s) and automatically you will start using a language and rituals to support this social construct.

- Personal investment: as a result you will be more likely to contribute your time, your efforts and your emotions. Your role has lowered the threshold for you to contribute.

- Identity: my role allows me to be specific about who I am within a community or a group and it becomes part of how I refer to myself. For example, I often introduce myself as:

- the father (a role) of 3 kids (a group / community),

- the founder (a role) of an online community,

- the member of a workgroup (a role) within a service club (a community),

- etc.

Ultimately, this is what membership results into: a building block for our own identity.

Influence is about Dignity

Members have to feel they can influence the community, and feel the community influences them. The statements of the survey dealing with this dimension are the following:

- Fitting into this community is important to me.

- This community can influence other communities.

- I care about what other community members think of me.

- I have influence over what this community is like.

- If there is a problem in this community, members can get it solved.

- This community has good leaders.

It’s very easy to see a pattern in how influential people behave. In his 2007 book Influence, Robert Cialdini outlines 6 path to influence, they are reciprocity, consistency, liking, authority, social proof and scarcity. But behavioral patterns of influence is not what we are after. Rather, we want to find out how a community can enable its members to be more influential.

It turns out that we should be looking for ways that people can gain recognition and credit. Giving members the possibility to claim authorship over their contributions is important in this respect. For instance, when Xerox wanted to improve the participation of their engineers in their knowledge management system, they did so by giving engineers credit for their contributions.

Prior to that, Xerox staff was reluctant to use the knowledge management system because participation would be an added duty to an already tightly controlled workday. But then they provided engineers an ability to “author’’ their solutions. Soon, it became a professional peer process where the authors are recognized for their solutions.

Now, let’s take this logic one step further. Ultimately the need for influence can be traced back at an even deeper level: the need for dignity and the need to be respected. To quote Mimi Silbert, co-founder of Delancy Street – a nonprofit organization from San Francisco:

Nobody should be only a receiver. If people are going to feel good and be accomplished and be part of something, they have to be doing something they can be proud of. We ought to set it up as a circle, so you’re always receiving and giving simultaneously. That’s really the only way to become somebody, and everybody wants to become somebody.

In essence, this is what Influence is about: the possibility that community can be a place to reconnect to ourselves. Of course it all plays out through social transactions of credit, authorship and recognition – but when you hold still for a moment it is easy to feel the power of an undercurrent: a need to find re-connection with oneself through community.

Meeting Needs is about Invitation

The status and the competences of a member within a community need to be honored. Are members’ needs being met? Are those needs aligned with the needs of the community? In the previous article we discovered that reinforcement mechanisms for reaching and keeping high engagement of members are at stake here.

At this point we need to note that there is a fundamental difference between two reinforcement mechanisms:

- External rewards as a motivation system, which work really well in a predictable ‘if-then’ environment. This can easily be accomplished through mandate and authority.

- Internal rewards: doing things because they are interesting and because they give us a feeling of belonging. This will require a completely different dynamic to get going.

It is the second category of reinforcement we are after in communities. The statements of the survey dealing with this dimension are the following:

- I get important needs of mine met because I am part of this community.

- Community members and I value the same things.

- This community has been successful in getting the needs of its members met.

- Being a member of this community makes me feel good.

- When I have a problem, I can talk about it with members of this community.

- People in this community have similar needs, priorities, and goals.

The engagement mechanic to meet the needs of a community is embedded in a the dynamic of invitation – as opposed to the use of authority. This means people are invited to take up a role and be accountable for it. This also means that people can turn down the invitation, and this is precisely where the power of an invitation dynamic is situated. The fact that refusal is possible makes a participation valuable.

If people have joined the initiative by choice, the social contract has completely changed.

We are borrowing some wisdom here from Peter Block’s ‘Community – The structure of belonging’:

Invitation counters the conventional belief that change requires mandate or persuasion. There are six elements to a powerful invitation:

1. Naming the possibility about which we are convening

2. Being clear about whom we invite

3. Emphasizing freedom for choice in showing up

4. Specifying what is required of each should they choose to attend.

5. Making a clear request

6. Making the invitation as personal as possible

In the same chapter of that book Block asserts:

Invitation is not only a step in bringing people together, it is also a fundamental way of being in community. It manifests the willingness to live in a collaborative way. This means that a future can be created without having to force it or to sell it or to barter for it. when we believe that barter or subtle coercion is necessary, we are operating out of a context of scarcity and self-interest, the core currencies of the economist.

People need to be here by choice. Then – and only then – we can start talking about the nuts and bolts of engagement dynamics that are offered to us by the new field of expertise called gamification (as we briefly noted in the previous article).

Shared Emotional Connection is about Sense-Making

Shared emotional connection can also be referred to as ‘culture’ or as ‘sense-making’. It is about how members engage in the construction of the narrative about their community. This is a common and ongoing process of attaching meaning to events.

In practice, this comes down to making sure that members experience events together and create meaning of those events together. The statements of the survey dealing with this dimension are the following:

- It is very important to me to be a part of this community.

- I am with other community members a lot and enjoy being with them.

- I expect to be a part of this community for a long time.

- Members of this community have shared important events together, such as holidays, celebrations, or disasters.

- I feel hopeful about the future of this community.

- Members of this community care about each other.

The sense-making of the common journey is the ‘narrative’ and it can also be found in how stories are created and told. We could refer to this as the ‘Stone Soup dynamic‘. The Stone Soup story is an old folk story in which hungry travelers trick the local people of a town into sharing their food.

As they are confronted with villagers who are reluctant to share food or a place to spend the night, they ask for a flint stone to make Stone Soup. This requires a gallon of boiling water – and this is something they can easily trick a villager into. Repeatedly villagers come over to look and return with salt and pepper, and vegetables and beef, etc. Starting with a stone and each time prompting the villagers to taste and have them say: “You know, this could use a little … (seasoning, beef, vegetables,…)” which they then contribute. In the end everyone tasted and declared it was excellent.

This is how we get members to share their gifts, connections and passions: we need a stone to begin with and a reinforcement dynamic that is invitation-based. Every ingredient that gets shared makes the sharing of a next ingredient more likely. And this is how a common journey gets built.

Handgrips

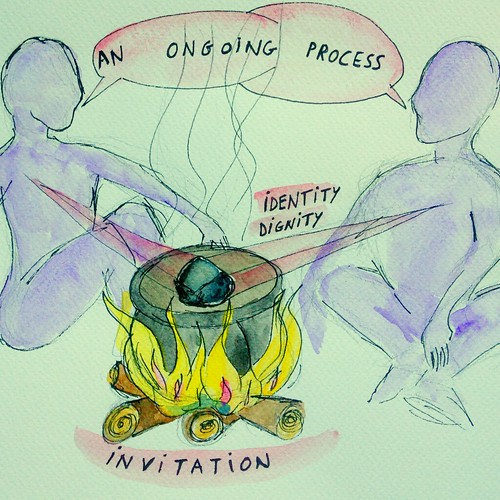

In this article we have attempted to look for the essence of each aspect of community and then to look for a handgrip that allows us to access it. As a conclusion we find that sense of community can be boiled down to four essential elements:

- Identity: ‘community is a building block of who I am‘

- Dignity: ‘community is where I reconnect to myself‘

- Invitation: ‘I am here by choice‘

- Sense-making: ‘I participate in the ongoing process’

It seems we need community to be fully ourselves. These four handgrips help us to diagnose and respond to what is going on in a community.