The purpose of this post is to zoom in on the attention that communities give to autonomy of their members. This is the one ingredient that makes the difference between authentic and inauthentic communities. But the prerequisites, the cost and the path to get there are less obvious.

We touched upon that ingredient briefly in the previous article when zooming in on the intrinsic motivators for members to make a personal investment into their community; i.e.: autonomy, mastery and purpose. In this article we will zoom in on autonomy, because it is pivotal in the creation of Sense of Community.

Autonomy is about the need to direct our own lives. It is the extent to which people show up by their own choice. The freedom for choice in showing up not only expresses our willingness to live in a collaborative way, but most of all it is a fundamental way of ‘being’ in community.

Peter Block is very instructive in outlining the consequences of being serious about autonomy. His books and talks on Stewardship and the use of power underscore a different way of thinking about how we bring people together and how we distribute power. Block puts a strong emphasis on autonomy and personal choice for engaging people into a change initiative.

The underlying theme in Block’s work is the orderly distribution of power in service of building the capacity of the next generation. That’s a pretty powerful statement that goes a little deeper than the classic “maximizing shareholder value”. Also: it’s less shallow. In his own words:

We need to build the capacity in people to manage the institution that can be theirs someday.

This raises the bar in terms of how we look at people: as human resources (an expense) or as human capital (an investment). In other words, Stewardship means that we start to treat people no longer as a means but as end in themselves.

What is Blocking Autonomy: Parent-Child Dynamics

Block starts with the observation that most organizations function as a pyramid structure with centralized power at the top and patriarchal control. Most of our management and measurement practices are designed to reinforce that control. There are benefits to this approach, amongst others: predictability, a focus on outcomes, results and measurements. This works perfect in a stable environment, but when things change our organizations are a bit slow to adapt and by their very design very reluctant to do so.

And that’s not all. The pyramid with it’s centralized control misses out on tapping into the potential of its people and everything that happens outside of the organizational boundaries. The intent to control and ‘take care’ of people is intuitive and good in nature but it blocks us from evolving towards organizations that are more resilient and adaptive to change. Here is why:

The care-taking approach leads us into a Parent-Child dynamic where someone is in charge and someone else is following. As a result we attach a lot of attention to bosses and leaders as our role-models. We look up to bosses as though they have all the answers… and if they don’t we are entitled to be disappointed in them.

We think leaders are responsible for the morale of their people and management practices are designed to confirm the idea that leaders create the organization. For instance, the way we conduct budget reviews and do performance appraisals. Block gives an example of a group of engineers who piloted an initiative that changed their organization without involvement of their leaders, because they would not have given the permission in the first place. Yet every time the story is brought up, people automatically want to attribute the success to management. We seem to have an engrained concept of leaders being at the centre of any organization. As he continues:

It is very hard to hold on to the notion that for progress to be made, leadership does not need to play a central role.

This does not mean that leaders are not important. But leaders just need to be brought back to life-size. It also means that we need to get serious about citizenship, i.e.:

I as an individual am going to be responsible for the wellbeing of this institution.

According to Block our current practices disempower people and take away the opportunity for them to hold each other accountable. Instead of asking “What can we create together?”, we end up helplessly asking “What’s In It For Me?”. There is a flaw in this dynamic and it is hidden in the well-intentioned patriarchal leadership response that is triggered by employees who act out their helplessness.

But what does it take to get from being stuck in a well-intentioned parenting model to an empowering partnership model?

The Cost of Autonomy

Block’s notion of partnership means that people can be responsible for their own actions and that bosses need to stop responding to questions of entitlement. We need to evolve from parent-child relationships towards partnership relationships.

“And then what?” you may ask. At this point we need to address the unspoken reciprocal expectations that bosses and subordinates have from each other. in short: it involves a lot of emotional work.

First, the mutual expectations of bosses and subordinates are unfulfillable.

- For members this involves acknowledging that their work needs to be satisfying by their own standards and their own expectations (the intrinsic challenge). When I look at my leader to affirm who I am and to give me my freedom, that leader will feel obliged to meet that demand to take care of me by setting boundaries and act in a controlling way. The emotional work for members is to stop looking at leaders for their wellbeing.

- For leaders this involves not affirming the longing to be taken care of. This is one of the toughest things to do because it goes against all parenting instincts. The emotional work for leaders is to stop rescuing because members have the capacity to motivate themselves.

Second, there is a cost to replacing the parent-child dynamic with a dynamic of partnership and it is twofold

- Accountability: For members, the cost to partnership is to sacrifice innocence and safety and to possibly live with guilt. This guilt comes from the fact that I am the one who is accountable when I no longer blame my leader.

- Loss of control: For leaders, the cost to partnership is to sacrifice control and possibly live with anxiety. This anxiety is caused by the sense of losing control of the results we feel responsible for.

So the price-tag of the freedom that is gained through partnership turns out to be quite high: accountability and loss of control. This is why many organizations, leaders and members will choose to hang on the status quo, simply because they are not prepared to pay that price. Some of us will never want to leave the comfort zone of entitlements and complaints about leadership. This is the bad news.

The good news is that it only takes a small group of people to start a change. Remember that Margaret Mead quote:

Never doubt that a small group of committed people can change the world. Indeed it is the only thing that ever has.

The small group is indeed the unity where change can take root. We don’t need consensus or a majority to shift a culture. Rather a small determined group of people who want to create in their unit an example of what the larger organization can become.

The minority of them who do choose to head in that direction will soon be asking for a strategy to get things going. How do we get from parent-child relationships to partnership relationships? Because after all, we are concerned about the benefits of autonomy: engaged members and a community outreach outside of the boundaries of the organization.

The Path to Autonomy: Invitation

Here is one thing to keep in mind when pursuing autonomy: nobody is accountable for things they have not chosen. Therefore the personal choice of people for showing up is fundamental to their engagement. Forcing or persuading people to join an initiative through our mandate is not the right strategy to foster engagement. It will lead people to look for a coping strategy to put up with the initiative as long as the eyes are focussed on them.

The alternative strategy for building engagement is called invitation. Invitation counters the conventional belief that change requires mandate or persuasion. There are two important elements of invitation to keep in mind: the price of joining and the fact that refusal carries no cost.

First, accountability is the price to joining an initiative or a community. Everything that has value has a price. Block notes that we need to be explicit about the accountability of joining. When the going gets tough we need to be able to confront people with the fact that they knew what the deal was and still showed up.

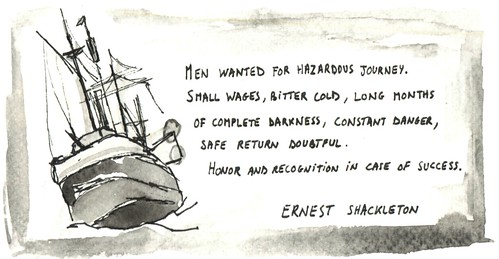

A good example of talking about the price of joining was the invitation of Ernest Shackleton who was recruiting for an antarctic expedition more than a century ago. Supposedly he ran an ad in the London Times that read:

Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.

No fewer than 5,000 people applied. That’s the paradox of being explicit about the cost of joining: it is specifically by addressing the hazardous nature of the journey that people will engage.

Second, it also means that people can turn down the invitation. This is precisely where the power of an invitation dynamic is situated. The fact that refusal is possible makes a participation valuable. Our job is to make explicit that refusal carries no cost.

The strategy of invitation confronts people with the choice they make on whether to create something new or to stay passive. If people have joined the initiative by choice, the psychological contract is completely different and they will be willing to contribute and engage with the community.

When we are explicit about the nature of our invitation, i.e.: the price of joining and the liberty of refusal, those who joined will be there by choice and their contributions to the community will be authentic.

That Moment When You Go: ‘OMG, I’ve been doing it wrong all the time’

This is the right time for organizational change practitioners to look at their toolboxes and best practices. If your toolbox resembles mine you are in for a humbling experience when you hold your practices against the light of autonomy, engagement, partnership and the strategy of invitation .

For starters, the way that we manage organizational change tells a lot about our underlying mindset. When we use the language of ‘enrolling’ people, ‘rolling out’ an initiative, ‘scaling’ an effort, etc. we are creating a context where someone is in charge and all the others need to follow. From the very outset we are limited by a control-mindset.

Furthermore, as organizational change practitioners we are trained to help our clients build and sustain care-taking parent-child relationships with their organization. Our role is designed to equip leaders with answers to the ‘What’s In It For Me’ questions. I don’t want to count the number of fellow practitioners who have this exact phrase at the top of their priority list every single day.

Maybe we should start looking at how we can maximize the opportunities for personal choice that people can have during a change? Turn that into a strategy of invitation… become explicit about the accountability of joining… the fact that refusing the invitation is OK… Because honestly… it’s the only chance we have at building the capacity of people to own the change when the project is over. In other words: this is the only chance we have at building commitment for installation AND benefits realization.

Sources used throughout this article:

Peter Block, The Right Use of Power: How Stewardship Replaces Leadership, read by Peter Block. Sounds True, February 2002. CD or cassettes.

Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2008

Series Navigation

<< Getting Serious about Community Development (Part 19)