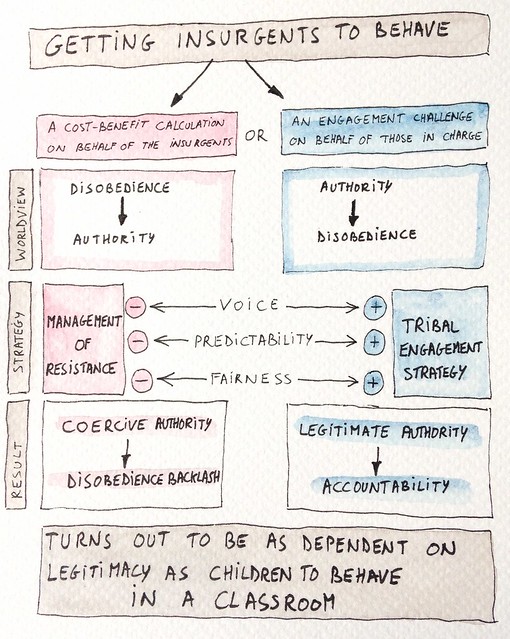

In this article we have a closer look at legitimacy and why it matters for engagement. Surprisingly we find that legitimate authority is a necessary precondition for accountability to occur within the target audience.

Why can certain people get things done in in a group or organization while others, even when they invest the same effort, cannot get any traction for the same initiative? Why do some people in a low position of authority have more impact in their organization than some individuals who are higher in rank?

Is it their courage? Is it their character? Or rather their charisma? Nope. It is something that is infinitely more linked to the way they relate to the context in which they are active; i.e.: their legitimacy.

Legitimacy refers to how well one’s authority is perceived. This matters a great deal if you want to engage people in an organization. The purpose of this article is to pull apart the different aspects of legitimacy so we can better understand how to develop it in people. What is lying at the basis of legitimacy? How does one obtain legitimacy? And how do you keep it?

Disobedience and Authority

It seems that authority lies at the basis of legitimacy. In the broad sense authority refers to the social status one has within a group: The extent to which a government has a grip on its citizens, the pecking order in a group of primates, or even the reporting lines on an organization chart.

In his 2015 book ‘David and Goliath’ Malcolm Gladwell offers powerful examples to illustrate that legitimacy is based on three elements:

- Engagement (‘Voice’): the need to feel like one has a voice: if I speak up, I will be heard;

- Predictability: the expectation that the rules tomorrow will be roughly the same as the rules today;

- Fairness: the authority has to be fair; all groups are treated equal.

He arrives at this conclusion by examining the civil war in Northern Ireland, where the repressive forces of the Brits were based on the assumption that authority is the result of a rational calculation of risks and benefits, not the extent to which their actions are justified. The initial intention of their presence in Northern Ireland was to support the police force temporarily in dealing with a local conflict. It turned out differently mainly because they were wrong about the justification of their own behavior.

To them, getting insurgents to behave was basically a math problem. They thought that if one are in a position of power you don’t have to care about how law-breakers feel about you; you just need to be tough enough to make them think twice.

They responded to disobedience with firm punishment. They had the force and the resources to do so. However it only made things worse. Gladwell quotes soldiers who were involved in the conflict and who assert that “most revolutions are not caused by the revolutionaries in the first place, but by the stupidity and brutality of governments.”

Inverse Cause and Effect

If we want to understand what lies at the basis of legitimacy we need to inverse some assumptions that we take for granted. For instance: we often think of authority as a response to disobedience. But disobedience can also be a response to authority.

Gladwell refers to a study of disobedience in classrooms that was conducted by the University of Virginia. They observed the behavior of children in the classroom as a result of the teaching style that was adopted by the teacher. Here, it was easy to see that when people in a position of authority (teachers) want others to behave (the classroom), it matters how they behave in the first place.

Teachers can use their authority to control the behavior of the classroom, or they can engage the classroom into an interesting activity that prevents the classroom from misbehaving in the first place. What teachers label as a ‘behavioral issue’ is often an engagement problem they are personally struggling with. Voice, predictability and fairness make a difference here.

This leads Gladwell to state the principle of legitimacy: When people in a position of authority want the rest of us to behave, it matters first and foremost, how THEY behave. Not surprisingly, getting insurgents to behave turns out to be as dependent on legitimacy as children to behave in a classroom. Legitimacy is all about the ability to engage with the target audience and to build on their knowledge. And that turns out to be easier said than done…

Tribal Engagement

To find out what this means in practice, we zoom in on the work of major Jim Gant. In the e-book One Tribe at a Time, he investigated the approach of the US forces to “secure the population where they sleep.” through the Afghan National Army and the Afghan National Police. Gant suggested to work with the tribal structures and traditions already in place and let the tribes protect themselves.

They employed a Tactical Engagement Strategy, which they called ‘one tribe at a time’. The first step of this strategy consists of communicating effectively, within the target audience’s cultural frame of reference. This includes studying and gaining a detailed appreciation of the tribes’ code of honor.

Tribal engagement is all about being on the ground and showing people trust and respect by truly joining forces with them. This is the true work of establishing legitimacy and it goes way beyond the narrow definition of tasks that is normally used when deploying projects. For example, the list of essential tribal engagement tasks includes:

- Establishing and maintaining rapport with the chosen tribe in the area.

- Providing a permanent presence that the tribes can rely on.

- Facilitating tactical civic action programs through the local government

- Report “Ground Truth” continuously.

In their own words:

“The world has to see the Afghan tribes and US soldiers working, living, laughing, fighting and dying together.”

In a project setting we would raise their eyebrows when looking at such a list of essential engagements. Most of these would be considered ‘out of scope’ or would be taken care of superficially. Yet these activities turn out to make the difference between legitimate and coercive authority.

Gant argues that in order to reach legitimacy, we need to work with tribalism, not against it. In the closing thoughts of his ebook, he quotes David Ronfeldt, saying

“Many so-called failed states are really failed tribes.”

Translate this to the world of organizational change management and you end up saying:

“Many so-called failed changes are really failed communities.”

And this is why Social Architecture is crucial to successful change; because it is essentially about establishing legitimate authority.

Fair Process

But tuning into and respecting the target audience’s cultural frame of reference does not necessarily mean that we always seek for consensus with the target audience. In their 2003 article ‘Fair Process: Managing in the Knowledge Economy‘, the authors Chan and Mauborgne explain that legitimacy does not depend on consensus about the outcome. Outcomes matter, but no more than the fairness of the processes that produce them.

The three principles of Fair Process that they distilled are surprisingly close to Gladwell’s list of legitimacy elements:

- Engagement: involving individuals in the decisions that affect them.

- Explanation: everyone involved and affected should understand why final decisions are made as they are.

- Expectation clarity: requires that once a decision is made, managers state clearly the new rules of the game.

According to them, fair process does not set out to achieve harmony or to win people’s support through compromises that accommodate every individual’s opinions, needs, or interests. This is an important distinction, because it separates two types of psychological contracts:

- Distributive justice: People reciprocate by fulfilling to the letter their obligation to the company. The focus is on fair outcomes.

- Procedural justice: Fair process builds trust and commitment, trust and commitment produce voluntary cooperation, and voluntary cooperation drives performance, leading people to go beyond the call of duty by sharing their knowledge and applying their creativity.

It is the second type of psychological contract that we are after when we want to establish legitimacy. Have a look at the drawing they used to explain the difference:

Legitimacy leads to Accountability

Earlier, I have written about what it takes to reach the second type of psychological contract; i.e.: through invitation. The strategy of invitation confronts the target audience with the choice they make on whether to create something or to stay passive. Accountability is the price to joining and this is exactly where legitimacy links into it: legitimate authority is a necessary pre-condition for accountability.

So the next time someone asks you to diagnose why a certain platform is not gaining any traction with their community, the odds are that their own authority is not perceived as legitimate. They will be likely to respond in disbelief “What? After all that I have done for them?”

That is when you could suggest having a conversation about fair process versus fair outcomes. Further diagnosis could include having a closer look at their engagement strategy: have you been working within the target audiences cultural frame of reference?